Dave McOmie of Camas doesn’t claim to be a big Frank Sinatra fan. If he was, he might have hummed a Sinatra ballad of longing and uncertainty — “Maybe You’ll Be There” or “If I Had You” — while cracking a spectacularly difficult safe at a Tahoe resort a few weeks ago.

But McOmie, one of the world’s most successful and storied professional safecrackers, doesn’t allow himself to be distracted by celebrities, media scrums, security guards or emotional families desperate to uncover riches when he’s working, he said.

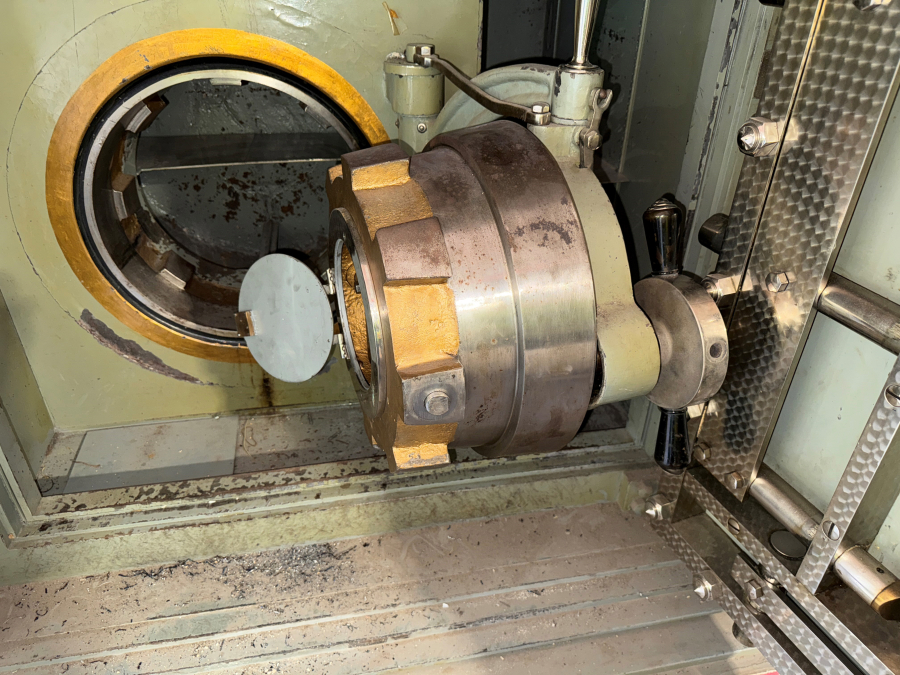

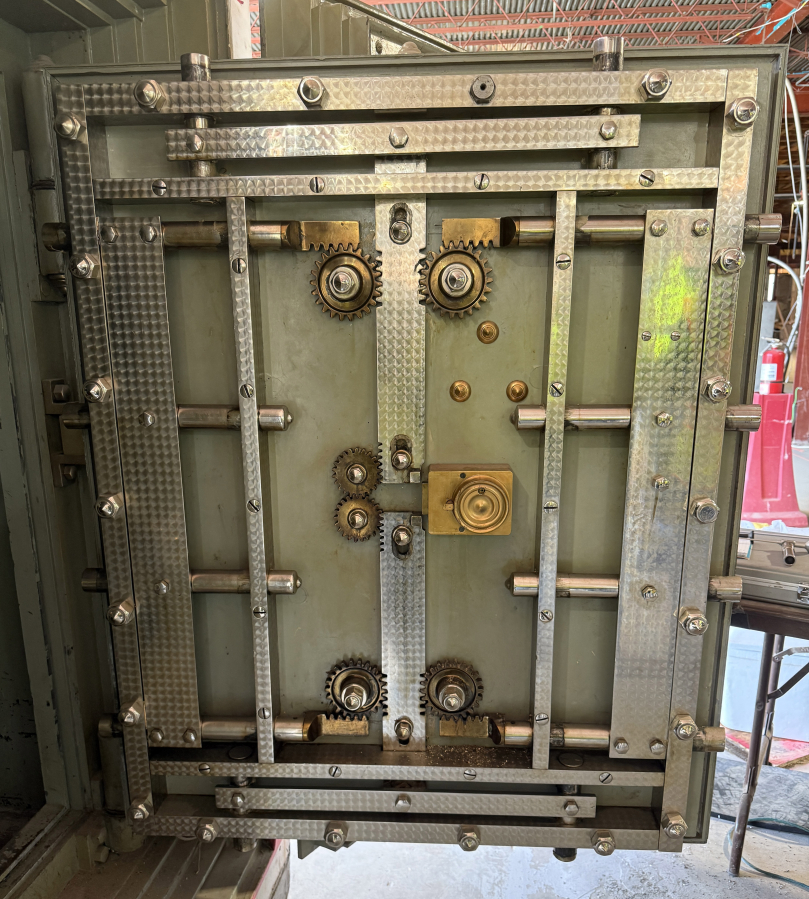

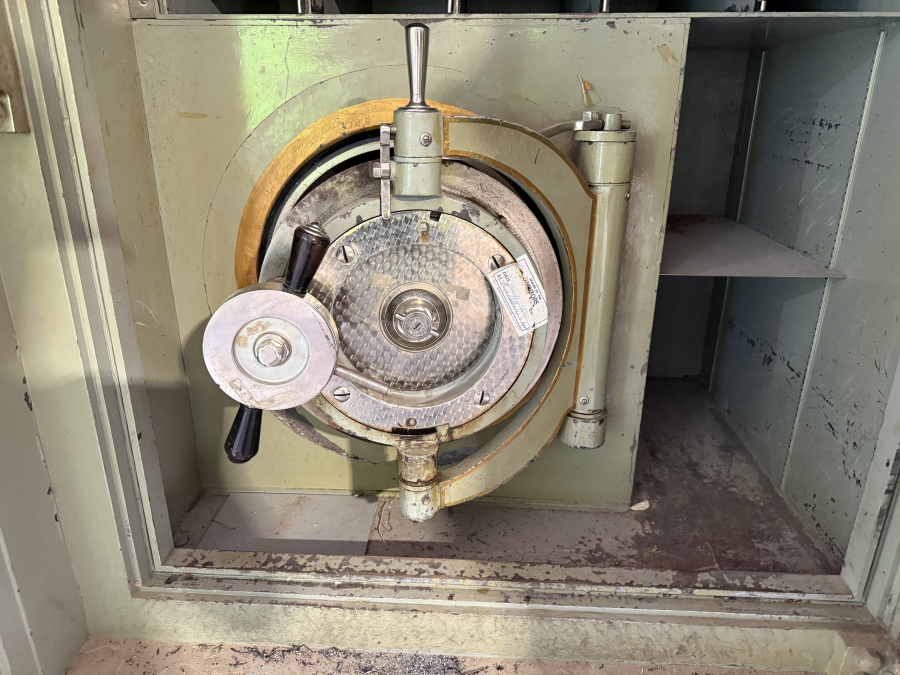

“I am hyper-focused on my opponent,” said McOmie, 68, referring to the safe he’s working on.

Those families are often who hire McOmie to break into a lockbox that supposedly can’t be opened, he said. Spouses or children are often eager to recover long-lost valuables or other unknowns after a death in the family. There are fortune hunters who gamble on mystery safes at auctions or even on Craigslist. And there are jet-setters whose jewelry or other valuables wind up accidently stuck in a hotel safe that refuses to cooperate.

When safes lock themselves down more or less permanently, it’s almost always because of human error, McOmie wrote in his 2021 memoir, “Safecracker: A Chronicle of the Coolest Job in the World.”